Connecting with old friends can be a mixed experience. Recently I went to my high school class’s fiftieth reunion, which had been postponed twice already due to COVID. When I received the second invitation last fall I dumped it into the trash can on my computer: why would I want to get together with these people from my past when I hadn’t connected with them over the last five decades? I had only one close friend from that time, Pedie, with whom I had remained in touch over these years; I didn’t need to go to a reunion that might rouse the specter of my unhappy adolescence in order to see her.

Then something unexpected happened: Pedie herself emailed me and asked if I’d accompany her to the festivities; or, to put it more aptly, she insisted that we go together to brave the waters of memory. Her adolescence had been difficult too, yet, as stubborn now as she had been then, she refused to allow me to say “no.”

And so the two of us journeyed, courtesy of Amtrak, to the suburb of Boston near my childhood home, back into the maw of all those years which had been so troubled for us both. She, too, was struggling with her own complicated history, perhaps feeling as anxious as was I. Would anyone remember us, or would we stand in a corner like the girls we’d been at our first mixer, hoping a boy—any boy—would ask us to dance.

Imagine my shock then, when several people expressed immediate delight to see me again, and some even embraced me. (It did not matter that these were mostly women.) I had never expected to talk to any of them again, and certainly not with such affection.

One of the woman who had dumped me and my inexpert tries at friendship during my sophomore year, now greeted me with excitement; another whom I was sure would not really remember me drew me aside and recounted the many wonderful memories she had of the time we’d spent together and which, in fact, I now remembered once reminded: how she had taught me to dance; how we had ridden our horses together in summer and winter alike; how we went to the same summer camp and slept in the same cabin. It seemed impossible that I had forgotten all this.

Memories are tricky. Sometimes we remember with affection and sometimes not, regardless of what the truth may have been. Sometimes memory itself is simply inaccurate: it can underline the negative and ignore the positive, or vice versa.

The pleasure of being among so many classmates was made even more special by the invitation I’d had earlier in the spring to give a short speech about the incredible teacher who had been an emotional pivot point for the entire class. Mr. Frank also meant a great deal to me personally and I was honored to be asked to recount our experiences together, first as a representative of the class of 1971, and then in his role as a mentor to me.

During my senior year, Mr. Frank seemed to sense that I was a “gifted” student who was having trouble at home with her mother. I was writing poetry at that time—probably ill-advisedly, considering the fame of my Mom. There was no way I could transcend her “shadow,” and perhaps he intuited that.

He asked the principal whether we two could meet once a week for a one-on-one tutorial wherein we would discuss a wide variety of authors and look at my poems, as well. This would be the first time I had ever shared what I was writing with anyone other than Anne Sexton.

Mr. Frank’s attention could not have come at a more valuable time. Shy and vulnerable, I was just about to venture into the broader world of college. He helped me to recognize my own talents in the writing world, and perhaps even foresaw that I would go on to focus there. He was my first mentor outside of the gigantic figure who lived in my house, who couldn’t really be my mentor, because she was my mother.

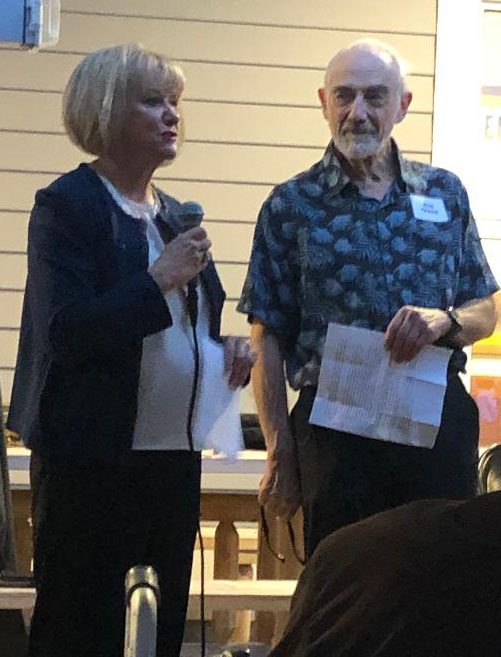

As I tried that night to describe the special attachment I had to Mr. Frank, I could feel him shaking his head as he stood beside me. Shortly afterward, in his remarks to the class, he described how much it meant to him to be honored by us all. Then, he actually mentioned the tutorial we’d shared, and with both humor and humility described the way he’d felt superfluous because I had a Pulitzer Prize winner at my right hand who was also counseling me.

Despite his demurral of his invaluable influence, he has continued to be one of my champions throughout the years, reading my books, as well as Linda’s Letters, and offering incisive commentary, for which I’ve always felt grateful. I hugged him as he finished speaking, and reiterated privately how much our interactions have meant to me over the years. I think he believed me—at least in part—by then.

And so I learned this weekend that I can take pleasure in memories I’d only wished to forget. I suddenly saw that although my home life was difficult back then, there had also been a side to my world that was bright.

As Pedie and I took the train back again, satisfaction buoyed our mood as

we enjoyed our sandwiches and did The New York Times crossword puzzle together. How grateful I was that she had been intuitive enough to sense that we would discover pleasure in our past, at last.

Yours,

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!