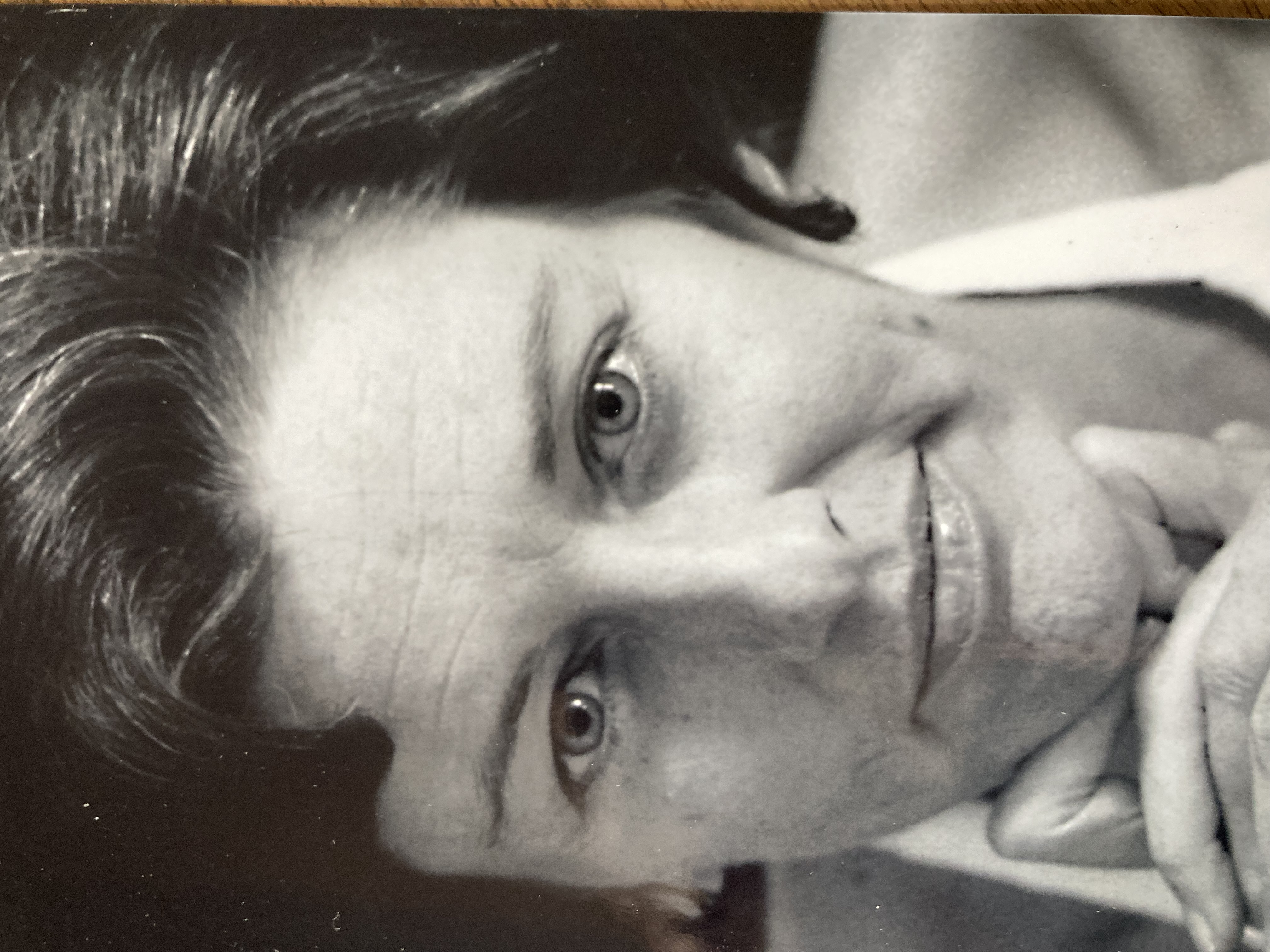

On the table in my study I’ve propped a photo I recently found of my mother next to one of my younger son. Her hair is dyed black, but is nevertheless tinged with silver around her face, and has been set in the style of the times: with curlers and a teasing comb and shellac from a lot of hairspray.

Her face rests on her crossed fingers, hands cradling her chin. Her expression is a mystery to me this morning: I am finding it hard to read her. The photo was taken when she was forty-five, some forty-eight years ago.

But then, quite suddenly, I see how soft her eyes are, filled with what I now, in my sixty-ninth year, can at last identify. Hugging the photo against my chest, I perceive for the first time what has been there all along. A few weeks later, on the sort of raw day that comes barreling in during late winter on the East Coast, my friend Sophie and I sit in my kitchen, mugs of tea warming our hands. I hand her the photo.

My mom committed suicide the year I turned twenty-one; I was a rising senior in college. Sophie’s father had been a suicide when she was a few years younger than I: the similarity in our lives is something that has always bonded us together. Suicide is such a desperate act, one governed by indelible mental illness—and often one borne of both anger and misery. Nevertheless, the two of us had only rarely talked about our parents’ precipitous deaths.

“You know, despite everything,” I say, leaning over Sophie’s shoulder. “I can see forgiveness on her face.”

She hands it back, quickly. “It seems as if you should be forgiving her, not the other way around.” Her voice is angry. “I don’t have a single good memory of my father. And the way it ended—I’ll never forgive him for that.”

I go silent for a moment. “Not one good memory? There must be one good thing.”

She shakes her head. “Nothing. Not after what he did. And you shouldn’t forgive her either.”

“But I do,” I respond. “There are a lot of good memories.”

“How is that even remotely possible?”

I pause again. “It’s possible because forgiveness works in both directions. Isn’t acceptance important in order to grow?”

“I’ll say it again: what does she have to forgive you for?”

I had had to put my mother behind, to leave her destroyed and without anyone to care for her in her most lonely hour. I could not have survived under the weight of her mental illness and her alcoholism at the very end had I not. I knew this, but it didn’t take away the pain of having deserted her at her most vulnerable.

“Don’t you see? I left her alone,” I said, tears beginning. “I left her alone to die. I need her to forgive me.”

Sophie says nothing, just looks away.

“I couldn’t help having to do it.” I wipe my face with the tissue she pulls from the Kleenex box on the counter and hands to me. “I know I had to protect myself—but that doesn’t make the tragedy of it any easier to deal with. Our lives aren’t only the sum of the things we leave behind.”

She gives a short laugh. “So that makes you think we owe them something?” She swivels on her stool to look at me head on.

“I think we owe it to ourselves.” I sigh, wishing I could be more articulate. “Forgiving is a way to heal. But it takes kindness. And maybe mercy.”

“You can’t heal from something like a parent’s suicide—I just don’t believe it. You’re rationalizing.”

“If you want to do it badly enough, you can.” I put my hands around my mug of tea, but it’s gotten cold now. “Forgiving her is just another way of forgiving myself. It’s the way I look for the good memories.”

We sit there saying nothing else, each shuffling through our own history. After a while, I put my hand over hers. “Forgiveness cleans out the hurt, cleanses your soul. When you’re finished, well, you feel stitched back together again.”

Sophie looks away, and I think to myself that she just isn’t in the same place I am—and she may never be. That’s her choice, even if it seems a sad one to me. But maybe, just maybe, eventually she’ll find a little bit of peace. Thank God I have.

Yours,

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!