I rode the wave, rising toward its rolling crest, and then dropped down into a gulf of pain. I was thirty-one years old, and it was a pivotal date for me: October 4, 1984. The day has just passed again in 2021, but that October Friday so long ago remains sharp in my memory—as sharp as if it had just occurred two days ago.

I had gone into labor with my second child in the very early hours that morning but I didn’t wake my husband. It was too early, I decided—a long time before we needed to leave for the hospital in Manhattan, which was an hour away. Six o’clock brought contractions at five minute intervals; I made a casual remark to my husband that my labor had begun, but that the baby’s arrival wasn’t imminent. He relaxed—after all, we had done this before.

In contrast, my labor with my first son had begun in the early afternoon and then lasted for the following thirty-six hours. I had gone to the hospital too early, only to discover I was only six centimeters dilated. Because my amniotic fluid was leaking, the obstetrician confined me to bed. No walking around the corridors to hasten the birth. The fetal monitor strapped around the mountain of my belly tethered me to the sheet, keeping track of the baby’s breathing and heartbeat.

I began my Lamaze breathing. But by the time eleven p.m. arrived, I was exhausted and the pain had taken over, though I was only five centimeters dilated by then. My husband and I were determined to avoid an epidural—a mild anesthesia that might affect the baby and also make it difficult to push through the last phase of labor.

Popular opinion in the eighties scorned any woman receiving medical intervention during labor. Instead, birthing rooms were far more common rather than hospital beds and O.R.’s; even a few radical underwater deliveries were done in home bathtubs. Jim and I had practiced the more common Lamaze method in daily sessions following the prenatal classes we attended every week. A “natural birth” seemed safer for the baby and would require nothing except fortitude on my part.

Not quite. It took some twelve hours more before it was time to push our little boy out into the world. And that phase alone then took over two hours. And so I learned a valuable lesson with Nathaniel’s birth: don’t go to the hospital too soon; take your time at home; walk around the block a bit; spend your last hours as a threesome. A new life and a new family is about to begin.

This October 4th in 1984, the three of us had indeed had a long walk, scuffing our sneakers down the sidewalk through clouds of crackling leaves. Taking Nathaniel’s hands, Jim and I swung our eighteen month toddler back and forth between us.

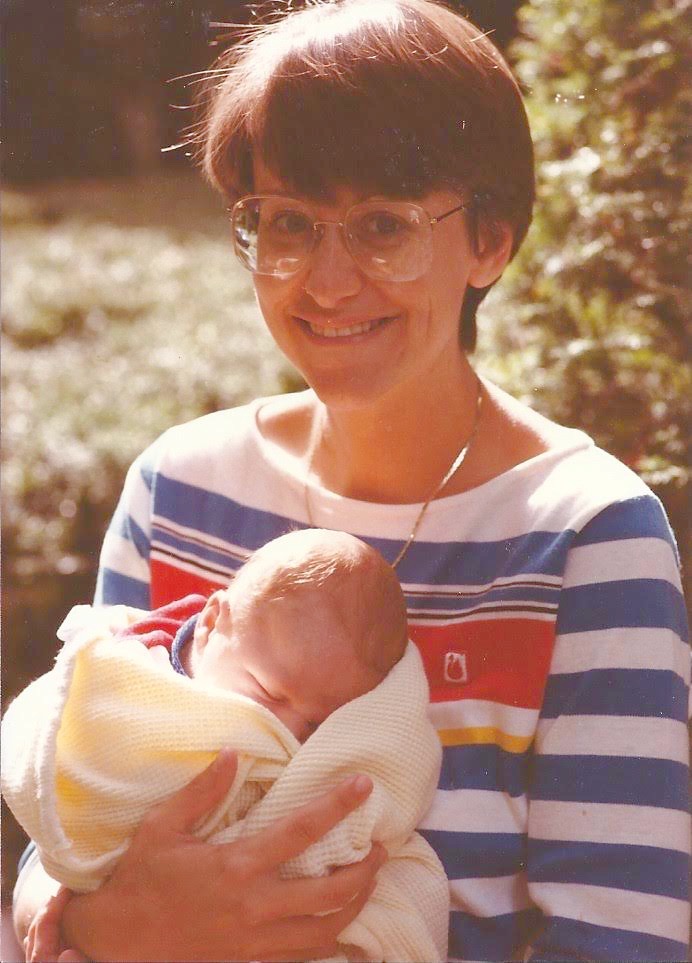

We arrived at the hospital just in time—my contractions were two minutes apart—and the doctor on call scolded me for waiting so long. Throughout the pain of labor and not until I held Gabe in my arms a miraculous four hours later, I had just one thought: October 4th in 1984 was the anniversary of my mother’s suicide ten years before. She had left our world during a late afternoon very similar to the one enjoyed by our family.

During my pregnancy I had wished that Gabe would be born on this same significant day; he was two weeks overdue and I felt certain that I had held him in my body for those extra weeks on purpose—until I could reach the afternoon of October 4th. I believed that where a life had been extinguished, another life would now roll in.

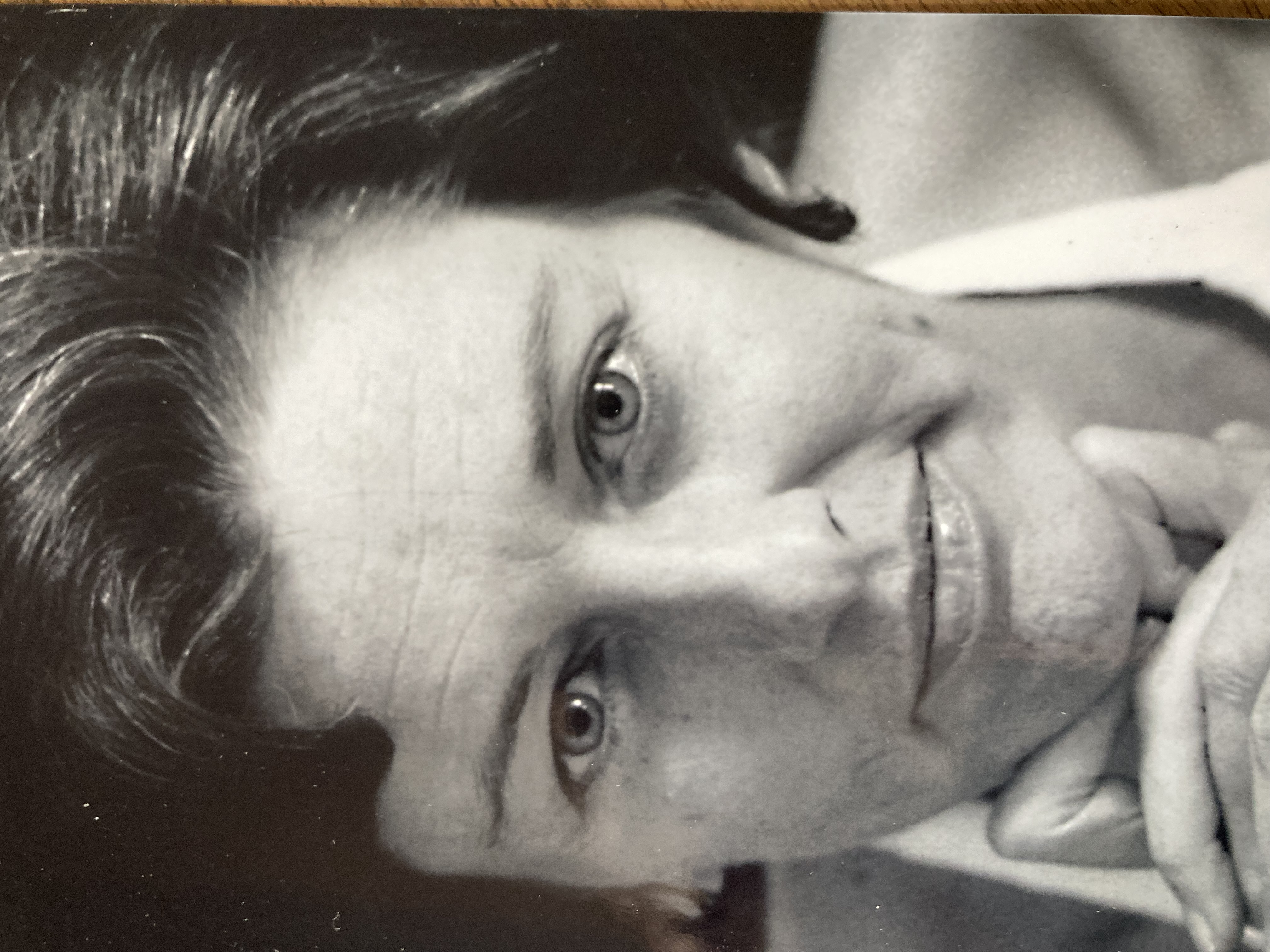

People always react with sadness when I tell them about the confluence of the two dates. “How hard for you,” they remark, with sympathy. They envision me bringing in a cake, singing my second son “Happy Birthday” with tears gathering at the back of my throat. I have grieved for my mother in many ways: when I graduated from college she was not there to celebrate; when I married she was not there to slip her gold bracelet on my wrist as a “something borrowed;” when I published my first book she was not there to hug me with pride.

But even as I hear the traditional melody begin every year on this particular day, I am not overwhelmed by the pain of her loss. I remember instead a great deal of joy—despite the conflicts we endured during her very last days. Laughter, tenderness, as well as friendship and a very mutual sort of adoration. As each year passes, on this day I reaffirm my vow that I will indeed share just such emotions with both Gabe and Nathaniel.

I try and explain to those friends who do not understand what October 4th means to me that when Gabe was born on the tenth anniversary of my mother’s death, I stopped mourning; instead, I began to rejoice. I am carried forward by the beginning of his life. It is no longer a day when her life stopped, each wave receding further and further as the months passed. Instead, the tide always comes up to the shore on which I stand this day, closer and closer until it wets my toes, moving in a rhythm that can only be described as magical. With it rises high the gift that only love can bring.

Yours,

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!