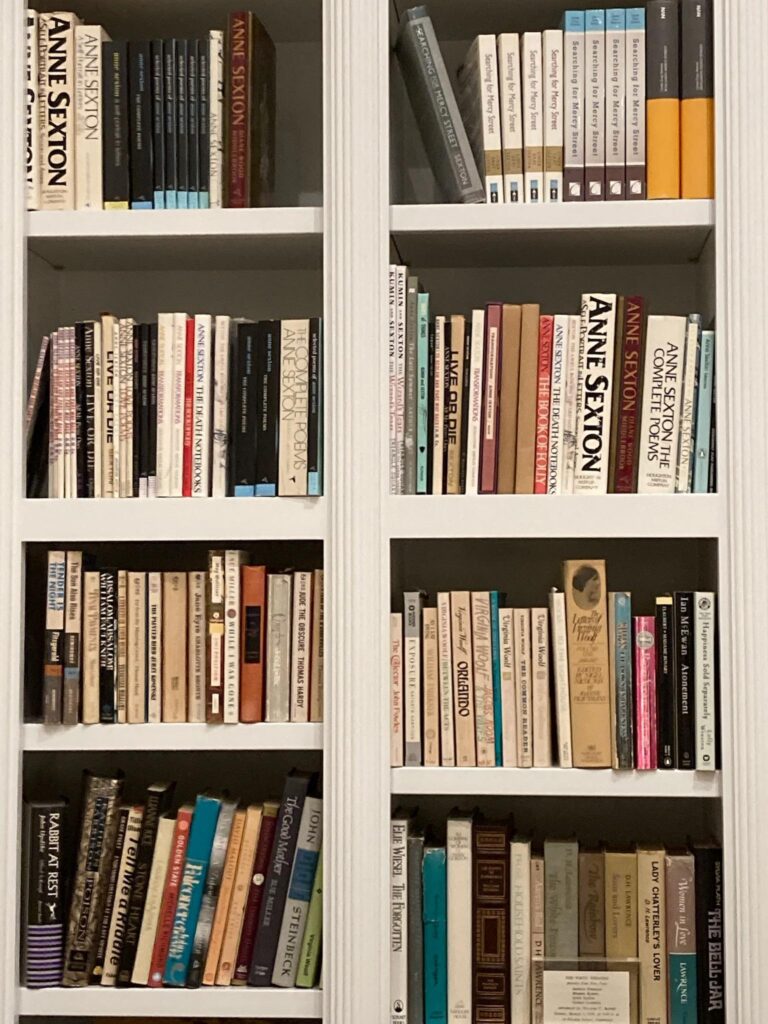

My mother’s name invades my writing room: the big, black, bold ANNE SEXTON jumping off the spine of Self-Portrait In Letters, a volume I edited when I was twenty-one, immediately after her suicide. Arranged on four of my many shelves are several rows of her books, both in English and in foreign translation, neither alphabetized nor in any chronological order; each she published either during her lifetime or was one I guided to life after her death in my role as her literary executor.

In my attic are two more stacks of cardboard boxes with even more copies, alongside the several cartons of my nine published books. I like to pass these books of hers along to those who love poetry, as well as my own work to those who love fiction and memoir. When I give her work, I give her life once again.

Despite all our difficulties during her lifetime and despite my anger over her suicide, I mourn her even now—having just turned sixty-eight: we all grieve our losses in different ways at different stages of our lives. As I pass the forty-fifth anniversary of the year she chose to leave us, I have put behind me both my despair and my rage at the way she chose to end her life so abruptly and moved on, with only sadness by my side.

I now mourn the friendship she and I might have had if only she’d had access to the medications so commonly available today, those that might have made it possible for her to fight her mental illness and not fail. I now mourn being unable to tell her how much I regret leaving her alone and lonely in those last months of her life—though that was all I believed I could do to keep my life afloat. I now mourn the loss of the wisdom she might have offered both to me and my own adult children as all of us grow older. I now mourn the joy we’d have shared as she poured us tea on a weekend afternoon, and we read aloud—a few pages of whatever each of us was working on.

I better accept and understand the torment in which she lived daily at the end, and in this way, I release her suicide and put to rest all those years of restless emotions within myself. Being her literary executor has given me that kind of peace. I celebrate my mother’s life and all it gave me in my own. Once I believed that if I did a good enough job with this task, I would in some way get her back. What time has taught me instead is that I’ve found myself.

I live too far away to return easily to the place where Mom is buried, but how I would like to go back there now to put my hand on the face of her granite marker: she may have happened to be my mother, but she was first and foremost a poet. “Talk to my poems,” she reminded me in a letter to “the forty-year old Linda,” written when I was only sixteen. “And talk to your heart—I’m in both if you need me.”

What a shock it is to realize that I have been her literary executor now for longer than she lived. I believe that I’ve been successful in my long-ago promise when I said “yes, Mom, I will do this for you,” when I took over as the guardian of this wild ride. Another letter, written to me on July 21 of 1974—my birthday, just before her death the following October—expressed her hope that the “spirit of the poems” would live on past both of us; that “one or two will be remembered in one hundred years.” And yet, over the near half century since then, her poetry has been translated into more than thirty languages, into operas, and plays, and songs. Less than ten years after her suicide, over half a million copies of her books of poetry had been sold.

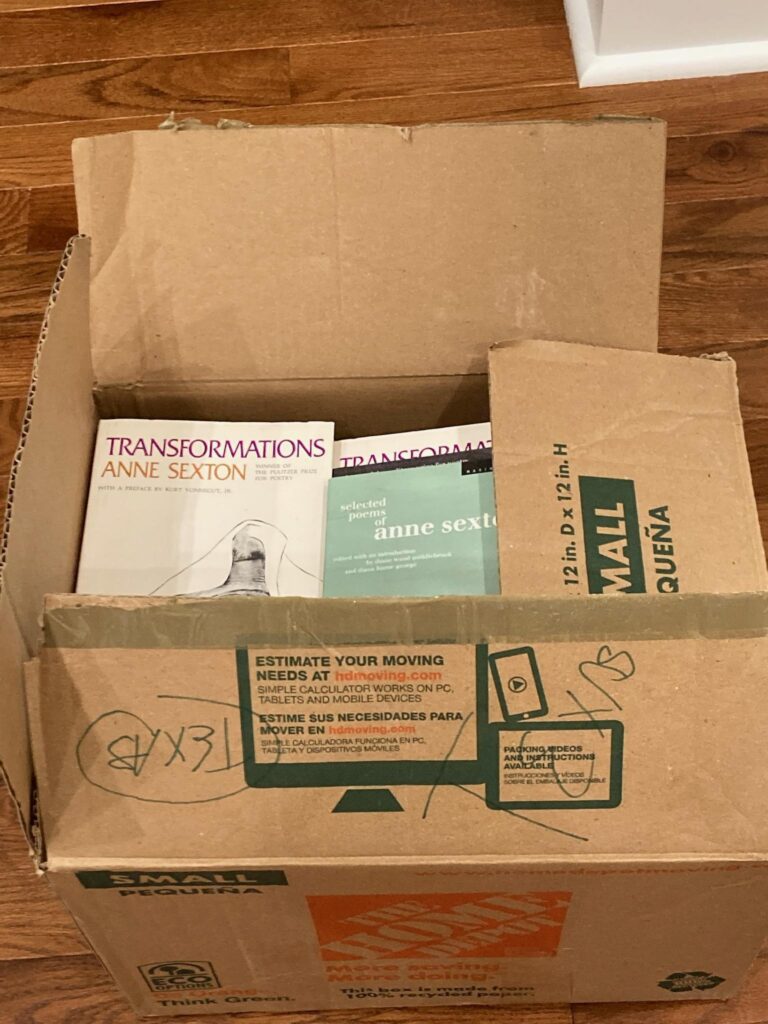

When I moved to my new home in June of this year, I was inundated with books, despite the fact that I had given away over seventy-five percent of them as I purged. This house had no bookshelves; I concluded that, despite my efforts, I would have to buy some to hold those books I’d kept. I had many copies of most of my mother’s work—many more than I needed. What to do with all of them? Of course, the answer was to give some of them away.

It occurred to me then that if I included some of Mom’s work in my last donation to Good Will, I would be spreading the poetry of Anne Sexton. Surely there were many people—perhaps those who shopped in thrift stores out of need, or those who shopped for bargains and had never before encountered it, or even those who would simply cherish a new volume of a favorite poet. And so I filled several boxes with her books and toted them over to my local branch. This brought me intense pleasure.

I have tried hard to protect her work and the story of her life, as well as to open it to those who wish to know more. I do this some of the time with uncertainty and error, some of the time with aplomb and finesse—but, above all, with commitment and love. This was her charge to me as a daughter and as a writer. To all those who wait at the steps of the libraries, eager to see her journals and her poetry worksheets, to all those who read her for the first time, I say: “Welcome to the world of Anne Sexton.” And thus, welcome to my world, as well.

Yours,

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!