Last week Dr. Seuss would have turned one hundred and seventeen years old. He was my childhood companion, warm and humorous, one of the many who helped me learn to read; and, of course, he was the writer who would in turn influence my children into an equally intense love of words. Now, I read his many books with my grandchild sitting on my lap. This pastime comes about, in part, by the lineup of battered Seuss on my shelves. I have never given away a single one.

But for many kids, this treasure chest of children’s stories will never be opened. Although his birthday gave rise quite some time ago to National Read Across America Day, created to excite children about reading, this year—under the pressure of our “cancel culture”—the estate of Dr. Seuss withdrew six more of his books. Both Amazon and E-Bay had decided not to carry them. They were to be “burned,” metaphorically at least, though perhaps they were indeed shredded—which is the fate of every book that does not sell and lingers in distribution warehouses.

But Dr. Seuss does sell. In 2015, 650 million copies had gone to good homes. This current wave of more books being “withdrawn” reminded me that another of my Seuss favorites, The Sneetches, had been banned earlier, and I wondered if I could buy one now; galvanized, I went to Amazon to order a copy for my grandson in New York. No real surprise when I found it unavailable.

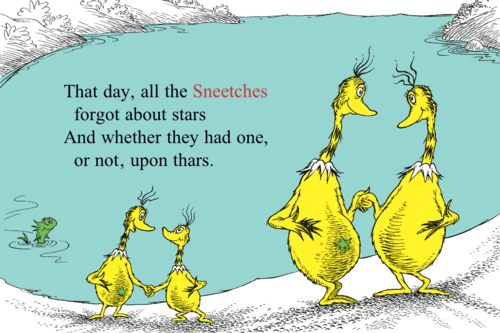

I’m sure that the charges leveled against The Sneetches are that it is racist. However, on reading my worn childhood copy again, I discovered that the story was anything but. It is, in fact, a clever satire about discrimination, written in 1961 for a pint-size audience, during the Civil Rights movement. The star bellied Sneetches, (who play the self-satisfied bigots in this drama), lord it over their plain bellied kin. As the story progresses, those with stars wind up having their stars removed, and those without stars have them emblazoned, and eventually all are mixed up as one equal tribe. The story’s final illustration is that of the Sneetches holding hands, and agreeing that the symbol on your belly, or how you look, or which group you belong to does not matter: what matters is the wonderful aura of closeness that being a Sneetch brings. The book closes this way:

“I’m quite happy to say

That the Sneetches really got quite smart on that day,

The day they decided that Sneetches are Sneetches

And no kind of Sneetch is the best on the beaches.

That day, all the Sneetches forgot about stars

And whether they had one, or not, upon thars.”

I wish I could contend that the example of banning Dr. Seuss is an aberration. However, increasingly, books are being pulled from library and bookstore shelves across the nation—as well as the giants Amazon and E-Bay. Here are just a few: Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl; Maya Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings; Poet Laureate Toni Morrison’s Paradise and The Bluest Eye; Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird; Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn; John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

I could go on and on, listing those that are classics, some of them written by the likes of William Faulkner and T. S. Eliot, or those that are more commercial, like Fifty Shades of Grey, or The Hunger Games. Shoulder to shoulder they stand, accused of a variety of wrongs, from being sexually explicit, to having “incorrect” religious portrayals, racial discrimination in either content or language, profanity, or police brutality. In contrast, one can, at this point, still buy a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf,instead of The Sneetches, a hypocritical situation I am certain the powers that be will remedy shortly—even though reading Mein Kampf is an education all of itself and therefore valuable.

In September, “Banned Books Week” will come once more, seven days committed to rallying people around the cause of remembering and supporting the First Amendment, which suddenly stands on shaky ground. This book-oriented week was conceived by the American Library Association Office For Intellectual Freedom; while it is true that many books do contain topics which make us uncomfortable or even angry, who is to say that we should not have them available to read? “Big Tech,” (as it is known in some circles, and which includes those giant corporations like Amazon and E-Bay), seems to be setting our national curriculum by eliminating ideas and points of view, narrative and entire bodies of literature. They appear to be intent on shutting down speech and writing that they deem offensive. What a shame. What a crime.

Suddenly you can’t choose which books you’d like to read to your children, even if you intend to set them in a historical and socially aware context. It strikes me that the important question here is not whether it is Amazon’s right to stop carrying a particular book for some currently socially acceptable reason, but whether it is good for us as a people, as a country. Shouldn’t I should be able to read The Sneetches to my grandson—just the way my neighbor is free not to?

When a corporation begins to shape the reading and thinking rights of Americans, something is wrong. I wonder how long it will be before books with alternative viewpoints will fail to even be published, simply because they cannot be distributed if they don’t fit a big company’s “Woke” agenda. With the loss of the give and take of spirited discussion and the debate of all sorts of issues, we will become an intellectually impoverished nation. The Sneetches is just a microcosm of the problem as a whole.

Dr. Seuss’s Mulberry Street, banned last week, does indeed center—as its critics contend, labeling it with the tag of social injustice—on the experience of an exclusively white childhood. But that isn’t the point. Other of Seuss’s stories portray racial stereotypes, and these are qualities that disturb me as I read to my grandson. To counter this, I talk to him about the problems those viewpoints provoke and the history behind them in simple terms.

He turns his face up to mine and thinks thoughtfully when I ask if there are any Asian kids in his class at school, and then we go on to talk about the character on the page, named a “Chinaman,” who has slanted eyes and carries chopsticks and how he, or others around him, may or may not act. I feel certain that he listens with attention to what I say, and will, as he grows older, allow this to shape the man he becomes: surely he will be an avid reader who is also socially aware. Only through discussing these issues, so well captured by the wonder of a childhood story, will he grow intellectually curious and learn new ways of thinking.

Is there a philosophy behind all this oppression? Or merely a list of enemies. Suppressing that which troubles us about some stories—those that have made up the backbone of children’s literature for decades—in order to relieve our anxieties, is an act of cultural violence. Why must we judge a book published so many years ago by its content or language, when it is so simple to put that content into a perspective that teaches. This is a sad time for kids’ books—and for free speech in general. Nevertheless, I will keep The Sneetches on my bookshelf, and, if their parents allow, read it to all the grandchildren who come into my life.

Yours,

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!