I haven’t been a devotee of poetry for over forty-five years now. My mother’s death did me in as a reader and writer of this often-enigmatic genre, making it impossible for me to enjoy the short mysterious lines studded with similes and its exacting attention to language. Poetry became too painful; too much of a reminder of the afternoons the two of us had spent in her writing room, pulling apart what she had written that morning and putting it back together in new ways. When she won the Pulitzer in 1967, we had danced across that room together, but her suicide in 1974 took all that joy from me.

Lined with bookshelves of knotty pine, softened by a pea green sofa with dents created by the warmth of our bodies, guarded by a Dalmatian in the shabby red armchair–this room had once held me spell-bound. Yet suddenly, I wanted only to close the door on it. It reminded me too much of her critiques–always kind, always generous, and always truthful–as she marked up my inexpert expressions of yearning, the kind of poetry any teenage girl might write. The room reminded me of those afternoons that forged a bond between us. How terrible that her passing took me, for a time, away from our connection, which I’d believed would always endure.

Once, poetry was like a river wending its way through the center of my life: it moved inexorably onward as I rafted down its surface, peering from above at weeds and fish, or running the cold rapids of wild water. I loved its rhythms as I loved almost nothing else. At night, with my homework finished, I spent hours in my bedroom with its pink-flowered wallpaper, creating line after line of metaphor, iambic pentameter, and slant rhyme. When I applied to colleges, I included ten of my best poems, believing there was some small talent buried in them that would help me gain admission.

Then came the day, in October of my senior year in college, when no one greeted me from the door of her writing room. What had been our sanctuary became a simple den with a television set on the shelf once again. I sat on the pea green sofa alone. In a letter written sometime before her death, she admonished me: “never be a writer, Linda. I will follow you around like an old gray ghost.”

I heeded her advice only partially, ignoring the intent behind her directive, and simply chose to stop writing poetry. Instead, I found a voice for myself in fiction and memoir. In the end, my love of creating language compelled me to continue. Of course, she turned out to be right, and she has haunted me in both the eyes of the reading public, and in my own as well. How sad that after I stopped creating poetry, I discovered I couldn’t bear to read much of it, either.

Yet, how I miss it, and her, and all that we shared during those desultory afternoons when we created such magic. Sometimes I wish the past away; sometimes I welcome it. Perhaps this part of me, the faithful poetry reader, has healed at last, though it took such a long time. Mom would have turned ninety this year, and I try to imagine what she would be like. In my mind, she is stuck at forty-five, dead now for as long as she had lived.

Everyone has memories that hurt, and yet we learn slowly that if we dig them up and allow them back into our consciousness, they can be joyful indeed. All of us can learn to read the metaphorical poetry of our lives again.

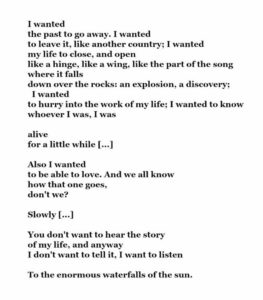

As I have said before in this newsletter, Mary Oliver is the poet to whom I turn when looking for solace. Because her work is so spectacular, I am willing to take the risk of remembering how I lost that languid time spent in Mom’s writing room–but also to honor the connection we forged as I continue to protect the trove of our love. Here is a fragment of “Dogfish,” from Mary Oliver’s Dream Work:

Though I have indeed told you some of the story, today I will stop now, standing under the waterfall of memory–and glad to be here, at last.

Yours,

Linda

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!