This coming Saturday, January 27th of 2018, is International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a date when people world-wide will observe the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, one of the Nazi’s most infamous concentration camps. The day stands as a symbol of the tragedy that transpired during their regime in World War II and of the world’s joy and relief that the period ended in freedom, if only for some.

Why mark such a day in our collective consciousness? Well, of course, the answer to that is obvious: so that we neither forget the mass extermination of six million Jews–as well as many others–nor repeat it. As a teenager, I was absorbed in Elie Weisel’s Night, an eloquent testimony that tackled both personal and philosophical questions, posed by a man who endured years as an inmate at Auschwitz.

One day in the kitchen of my best friend’s home, I was asked by her mother what I was reading with such intensity. I answered that the book was one written by a man who had survived Auschwitz. “I’ve never heard of the place,” she replied, and went back reading to her newspaper. I was shocked then, but I am not shocked now, as I realize that there are certain people, even in the world today, who are unaware–and who want to remain unaware.

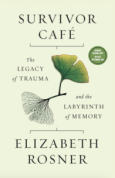

I am now reading another amazing book, Survivor Café: The Legacy of Trauma and the Labyrinth of Memory, written by Elizabeth Rosner, the daughter of parents who lived through the Nazi regime. Her mother escaped by hiding in the Polish countryside; her father survived his imprisonment in Buchenwald, a slave labor camp where 43,000 political prisoners and Jews starved or were worked to death, until the Allies liberated it in 1945.

Rosner addresses many genocidal holocausts, not just the one that occurred in Germany to her parents: the Cambodian killing fields; the destruction of the Armenians by the Ottomans; the killing rages of the Tutus in Africa; Syria today; 9-11; the lynching of blacks in years not so long past. But the story that interests me the most, predictably enough, is the trip she makes with her father to the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald.

It is an emotionally difficult journey for both of them, but one she was determined to make, despite her father’s reluctance to go back to this place that held such ghastly memories for him. Not surprisingly, it was an experience she can never forget, a personal one amid statistics; and she describes it in the sort of exacting detail that cannot help but open anyone’s eyes.

Yet, this is only a small part of her book, which also deals with those–often philosophers and writers-who insist that other peoples’ words cannot adequately describe this tragedy because they did not witness it themselves. What, Rosner asks, are we going to do once today’s survivors pass from existence if this is so? Who will be qualified to tell the vivid truths?

I think of Primo Levi, Elie Weisel and even Rosner herself, those who have struggled to use language as a way of shaking us up, so that we do not let this particular piece of history rest. And there have been others who confront the subject of different genocides throughout the years, equally as convincingly. Words are what we have to do this, our main tools–whether spoken or written–to capture such experiences.

After all, didn’t a chorus of words convince the public to observe an International Holocaust Remembrance Day to begin with, or to make certain we built a Vietnam War Memorial that stirs one’s soul with its power? It seems to me that language does something even more critical than simply describe an experience or impart information: it makes us aware so that we cannot turn aside.

If I had been old enough, or wise enough, to speak up to my friend’s mother that day in her kitchen when I was a teenager reading Night, if I had been able to make her put down her newspaper with even one story from Primo Levi about his years in Auschwitz, the truth she wanted to evade would have been inescapable.

Rosner herself has made this kind of response possible by writing her book–and so have innumerable others who bear witness with their testimonials that reek of the truth. This process now includes sons and daughters and grandchildren of survivors, those who speak of the ways in which their family was marked–and thus they themselves were marked–by history. In the end, Rosner says, “I carry the words; I pass them on. I listen to the stories and tell them again.”

In the end, don’t we inherit the stories? If the younger generations of today, as well as those yet to come, do not ensure that all these facts and emotions are carried forward, where will we be? Destined to repeat? Is it not our responsibility to make sure both the survivors and the dead are remembered and thus live on, using both their words–and our own? Because, as Rosner shows us with her attention to other like tragedies, all such recounting is part of one big story. The world’s story.

Please pause this coming Saturday, for even one moment, to observe International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Remember all you have heard of the world’s many genocides; decide to find out more about those you have not. Visit the museums and places dedicated to those who died so brutally, and listen to survivors speak in their own words on audio and videotape. Remember it all–for them and their families. But lastly, remember it for yourself.

Yours,

Linda

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!