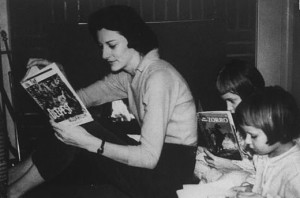

I was born into a home filled with shelves stuffed full of books. When I was a child, my mother, the poet Anne Sexton, frequently read aloud to me, and the first book I would remember well was a dog-eared blue volume of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, full of all its macabre horrors.

As I reached the early years of my adolescence, she showed me the public library, where I spent uncountable hours with novels and the biographies of famous women. I am not sure that I recognized at this point how much of a famous woman my own mother was already becoming, or perhaps I did, on an unconscious level. At the bookstore she told me there was always money for books–no matter how strapped we were–and bought me every one for which I asked. Eventually, when I was thirteen, she won the Pulitzer Prize, at last becoming an icon in the world of what is known as “confessional poetry,” being read by thousands of those who identified with her candid poems about love and loss, mental illness, suicide, and her own personal truths.

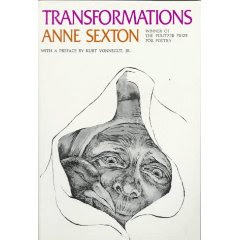

When I turned eleven, she invited me into her writing room, where our Dalmatian stood guard at her feet. There, she asked me what I thought of various poems, respecting my opinion and, after a time, playfully dubbing me her “greatest critic.” The two of us worked together on her book Transformations, which took the fairy tales of my youth and reinterpreted them. I chose the stories she would write about, and then helped her to revise them.

I began to write poetry and short stories, on which she offered her opinions. Curled up on the worn green couch in her writing room where she sat rocked back in her chair, her feet elevated on a bookshelf, I listened seriously. She was a gentle but hard critic. I grew used to writing many, many drafts and revising endlessly, as she did, but I enjoyed this part of the process; I rewrite, to this day, in both my fiction and my memoir, as mercilessly as I can. It is the first draft that I find difficult, because she taught me that to for it to “work,” you must tap down into the unconscious, and sometimes I find that difficult to access initially–though those depths have become a distinct aspect of both my fiction and my memoir. It was hard to be a writer, I discovered, and I never had one poem or short story published, but I persevered, determined to find my own voice.

When eventually I did find that voice, and my own first books were published, (initially a non-fiction book about the choices women of my generation were making between family, career and their own personal needs in the seventies, and then later, four novels and three memoirs), I found one piece of her advice equally invaluable. My mother always told me, “Linda, tell it true. Tell the whole truth.” As I went forward to tackle memoir, these words stood by me, inspiring me as I dealt in prose with topics she had confronted in poetry. My three Dalmatians also stood guard at my feet. I, too, wrote of family secrets, my own mental illness, and even the process of coming to forgive her for her eventual suicide. These were footprints I found myself unable to refrain from following.

Ultimately, I am extremely grateful to my mother for having given me my start as a novelist and memoirist. Still, she always told me, “Never be a writer, Linda, because I will follow you around like an old gray ghost.” Yet she also said, “Live to the hilt! Be the woman you are!” I found myself listening nearly helplessly, without choice, to the latter. Despite continual problems with others identifying me solely as Anne Sexton’s daughter regardless of my own success, I have learned to make my own way toward peace and acceptance with the inevitable “gray ghost” she did indeed turn out to be. I bless the days I spent at her knee.

Yours,

Linda

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!