It’s Father’s Day this coming Sunday, and considering that I spent Mother’s Day writing about Mom, it seems only fair that I give Daddy equal attention.

Now that he is gone, closing his eyes for that final time on May 11, 2012, I have all sorts of memories engraved in my mind and on my soul as I approach this “Hallmark Holiday.” Those I experience most vividly are: delight at his dry wit; exasperation at his stubbornness; appreciation for the affection and determination he lavished on me as he taught me how to cook; impatience with his impatience; disappointment over his irritability when he tried to help me with math homework; fear at his quick temper; gratitude for his dedication in coming to every one of my horse shows; pleasure in sharing the care of our marine saltwater fish tank; frustration with his strict rules and curfews; pride as my awed high school friends named him the most handsome Dad around; love for his consolation of teen infatuation gone bad; intense need for his tender support through my three miscarriages; and joy as he became a fabulous grandfather to my sons.

No one, but no one, was like my Dad.

We were both voracious readers, but we didn’t share any interest in the same books. He was stuck on John Le Careé, Agatha Christie, spy novels, and the slew of authors who drew incisive portraits of Africa. A safari there had been one of the highlights of his life, as he was an avid hunter.

When he grew into his senior years, I moved from his beloved Boston to New York, and then across the country to California, where I have lived for the last twenty-five years. Our time together back in Beantown became limited to only a few visits a year. What stood between us were three thousand miles, my responsibility to be home for my kids on a regular basis, my anxiety over flying, and a seven hundred-dollar round-trip ticket when neither of us was flush. As he grew older, plane travel became onerous for him.

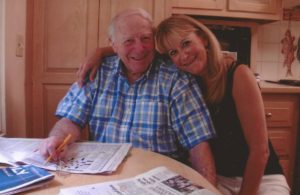

When I did come to see him more frequently in his later years, the increasing pain of bone-on-bone arthritis in his hips and hands crippled him; eventually oxygen was necessary to help with his COPD and emphysema–even though he stubbornly resisted this. And so we simply sat and read together in the living room, played Gin Rummy on the coffee table, or tackled a crossword puzzle after breakfast in the kitchen. Though I tried to help out with “down and across,” I was lousy at it and he–who had never finished college–crowed over his ability to best his daughter, a Harvard graduate.

The fact that we had such a short amount of time together during this last period of his life is one of the few things I regret, though I don’t consider regret to be a very productive emotion and generally try to accept it and let go. But now I feel I should have made more of an effort to overcome the obstacles that separated us.

I was at the Dalmatian Club Of America National Specialty Show in Oklahoma when I got the phone call from my sister who works at Hospice Cincinnati. “You need to come home,” she told me. “Right away. Dad has pneumonia and we’ve decided not to treat.”

Even though he had had a “DO NOT RESUSCITATE” sign on his refrigerator for the last five years, even though he had been in and out of the hospital innumerable times recently and told us each time he returned: “Old age is hell–just take me out in the backyard and shoot me,” I was still unprepared. Shocked at my sister’s words. How could we not treat a simple and curable illness like pneumonia?

But he was clear in his mind. Adamant. Gone were his years of hunting a deer, dressing it and dragging it miles to camp in the wilds of Nova Scotia. Gone were his weekends of mowing his beloved lawn, planting flowers for the short Boston summer, and mulching in the roses to prepare for winter. Gone were his days of tennis and golf, and a martini on the eighteenth hole with his friends. He’d had enough.

I flew in on the first plane I could. At Dad’s bedside, my sister and my stepmother were waiting for me, caring for him at home with the help of hospice. He was still conscious. “Oh, Linda Pie!” He welcomed me with a smile, and held his arms out to me from where he lay on his pillow. “You’re here at last.”

By the next afternoon, however, and all too quickly, talking proved impossible. He lapsed into unconsciousness, as his compromised lungs filled with fluid. My sister, stepmother and I banished hospice into the background and began to nurse him ourselves around the clock, each taking a shift. We changed his bed pads, moistened his lips, sponged his forehead, administered his painkillers, and held his hands. Dad lasted another twenty-four hours. The three of us were peaceful as we saw him off, by ourselves, on the last voyage he would ever take.

The night Daddy left us was a special one. Unlike my mother’s death, so abrupt and unresolved, my father’s was marked by an intense emotional closure. Together, we three kept vigil beside his deathbed, holding his hands, murmuring that he wasn’t alone. And when that last breath came, caught and held in his chest, never to be exhaled again, we were beside him.

After he was gone, we did not rush to call hospice. We simply sat next to him, cried, and traded stories, drawing memories from deep within the treasure chest families often open only in such circumstances.

Before the coroner came, it was important to me to bathe and prepare him for his final ride. Joy and my step-mother agreed. And so, as legions of women before us had done in less modern times, we took basins and towels and soap and washed away the signs of death. I removed his diaper, combed his hair, and then we put him into clean p.j.s. He was ready to make his last journey. Just as he had brought me into this world, I now helped take him into another.

Hemingway wrote, “Write hard and clear about what hurts.” Dad would have said it in a slightly different way, but one similar also to my mother’s advice to “tell it true.” For many years, he entreated me to “tell me your all.” All three of these exhortations say exactly the same thing. Dad meant for me to talk about the dark as well as the light, the joy as well as the sadness, the truth about whatever I wanted to tell him. My “all.”

On this Father’s Day, four years after he is gone, I am finally ready to talk about these difficult feelings. The Bob Dylan song below is one Daddy might have played to me as a lullaby–had he liked the musician’s scratchy voice. He was more a Frank Sinatra kind of guy. Regardless, he really would have loved the lyrics.

May God bless and keep you always

May your wishes all come true

May you always do for others

And let others do for you

May you build a ladder to the stars

And climb on every rung

May you stay forever young

May you grow up to be righteous

May you grow up to be true

May you always know the truth

And see the lights surrounding you

May you always be courageous

Stand upright and be strong

May you stay forever young

May your hands always be busy

Your feet always be swift

May you have a strong foundation

When the winds of changes shift

May your heart always be joyful

May your song always be sung

May you stay forever young

Forever young, forever young

May you stay forever young

I apologize for the length of this newsletter, but my Dad deserves every word. And so I close with this, and tell him what he already knows: “Daddy, in my heart, I’ll always be singing your song.”

Yours,

Linda

Have a comment or feedback? Talk to Linda!